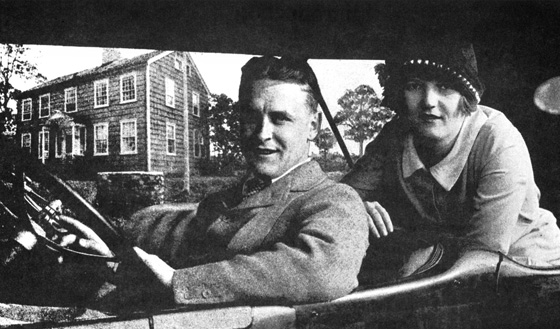

Scott and Zelda embodied the wild and glittering romance of the Roaring 1920s, and the restless rebellion of their generation. The era was marked by endless parties, daring style, and glamour, all sparked by an economic boom, which brought a spurning of social mores and a cultural awakening.

In his novels and many short stories, Scott captured something essential about America and became an inspired chronicler of his age. The decade was, in his words, “The greatest, gaudiest spree in history.” And the Fitzgeralds were there to celebrate it. Together, Scott and Zelda became icons of the Jazz Age.

Their Relationship

Scott Fitzgerald first met Zelda Sayre at a dance at the Montgomery Country Club in 1918 while he was stationed in Alabama awaiting deployment to Europe and The Great War. Zelda was a beautiful, popular, and unconventional belle from a respectable Southern family. From the start, their courtship was both passionate and tempestuous. Zelda refused to commit herself at first and broke off their long-distance engagement at least once due to Scott’s uncertain finances and professional future. In the spring of 1920, however, Scott published his first novel, This Side of Paradise. The first 3,000 copies sold out in three days—it was an immediate bestseller. Zelda joined him straight away in New York and they married less than a week later. With the success of his first novel, Scott became an instant celebrity, along with his new, fashionable, and free-spirited bride. They were tastemakers, New York’s “it” couple. Zelda was charmingly wild, clever, and a modern, more independent woman—the quintessential flapper; Scott was a dashing, talented writer and spokesperson for their generation.

A Shared Artistic Legacy

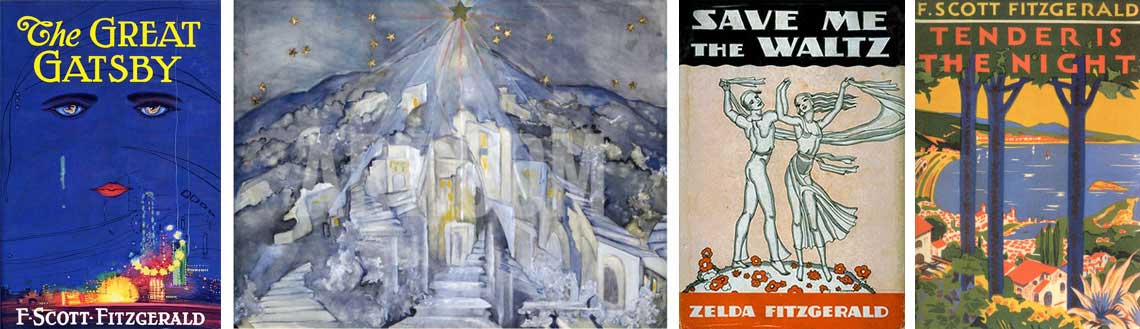

Scott completed more than 160 short stories and five novels during his career, including the iconic American novel The Great Gatsby. He was both a participant in and critic of the culture of consumerism and excess that marked the period he coined the “Jazz Age.” Scott and Zelda’s relationship was a driving force in their creativity. He viewed Zelda as a “true original,” and she was both muse and model for many of his female protagonists. Scott’s characters and story lines were frequently derived from life experience, and though both he and Zelda drew from similar raw material, which spurred some competition between them, the pair strove to support each other in their work. Scott encouraged Zelda’s own writing endeavors, which included dozens of articles and short stories as well as a novel, Save Me the Waltz, published in 1932. Zelda’s creative ambition and talent, however, were not confined to writing. While she and Scott lived in Paris, she rigorously studied ballet and was offered a position with the San Carlo Opera Ballet Company in Naples, Italy, though she ultimately declined the invitation. But perhaps Zelda’s most poignant and enduring creative legacy is her artwork, which consists of more than 100 surviving gouache and watercolor paintings that she produced in her own whimsical style.