In the 1920s—les Années Folles—Paris celebrated diversity and embraced the extravagant. It was one of the great cultural capitals of the world—a gathering place for those who would emerge as artistic and literary legends of the twentieth century. And it was the birthplace of The Lost Generation.

The Lost Generation

In 1924 the Fitzgeralds found themselves in Great Neck, Long Island, some fifteen miles outside of New York City. The area was popular with the show business set who were flush with money and entertained lavishly. Scott and Zelda were enthusiastic participants in their roaring, glamorous parties.

For a couple of years Scott had been sketching a novel, a precursor to The Great Gatsby. He wrote to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, that he wanted to create “something extraordinary and beautiful and simple and intricately patterned.” To do so, Scott needed to escape the clamor of their current lives and make a fresh start. Post-war Europe, with its relatively low cost of living and thriving artistic scene, filled the bill.

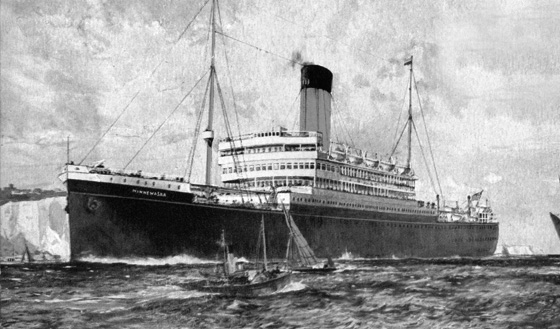

In April of that year, Scott, Zelda and their young daughter, Scottie, set sail for Europe. They rented a villa in Saint Raphael on the French Riviera where they became friends with a wealthy and worldly American couple, Sara and Gerald Murphy. Charismatic hosts, the Murphys frequently entertained at their Villa America, which overlooked the beaches of the Mediterranean. They introduced the Fitzgeralds to a wide circle of musicians and artists, including Cole Porter and Fernand Léger. The Murphys later inspired the main characters in Scott’s fourth novel, Tender Is the Night. “One could get away with more on the summer Riviera,” Scott wrote to his editor in New York, “and whatever happened seemed to have something to do with art.” It was here that the extraordinary novel Scott had set out to write, The Great Gatsby, was completed.

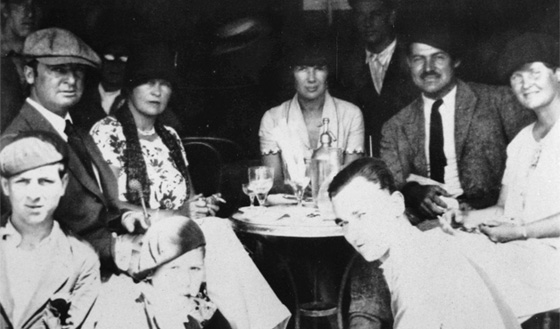

Once Gatsby was published in 1925, Scott and Zelda took an apartment in Paris. At the time, the city was home to a confluence of technology and creative energy that would come to define “modernism” in the early twentieth century. It also lived up to its bohemian reputation as a place of post-Victorian exuberance—the champagne flowed freely and the nightlife was endless. The artistic crowd converged on Paris’ left bank neighborhood of Montparnasse—popular for its low rents, creative fervor, and abundant cafes.

It was in this thriving scene that the Fitzgeralds joined “The Lost Generation,” a title bestowed on a group of expatriate writers by Gertrude Stein, an American-born writer, avid art collector, and intellectual. Like so many in this cohort, members of The Lost Generation had survived World War I but had lost their brothers, their youth, and their idealism. In the aftermath of war a new realism was emerging, and they sought fresh voices and forms of expression. Stein nurtured this group and held regular Saturday evening salons in her apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus, hosting artists such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, and poets and writers, including Ezra Pound, John Dos Passos, James Joyce, Archibald MacLeish, Sherwood Anderson, and Ernest Hemingway. Scott became close friends with Hemingway and encouraged and promoted Ernest’s burgeoning literary career, often with more dedication than to his own.

In December 1926, after another year of travel between Paris and the Riviera, the Fitzgeralds returned to America. Scott’s place among The Lost Generation was secured, with Stein declaring him the “most talented writer of his generation, the one with the brightest flame.”